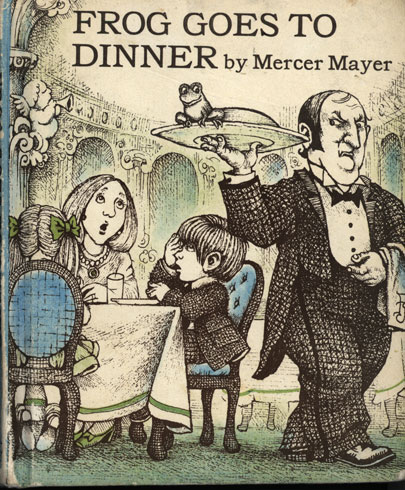

In the tradition of the Socratic dialogues, Kevin and I will jointly proclaim our reverence for Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird, creators of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Zander: I was first introduced to the Ninja Turtles by my neighbor, Mike McKenna, who said that 1) they were awesome, and 2) that the first issue was already worth something like

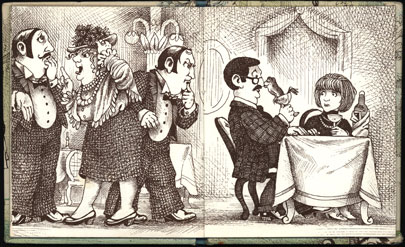

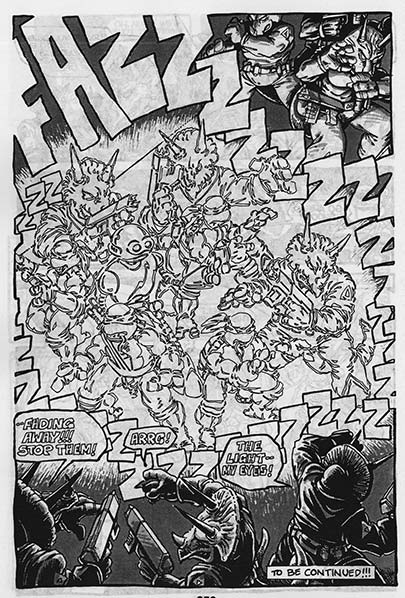

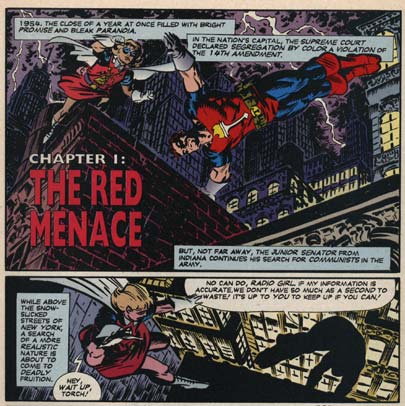

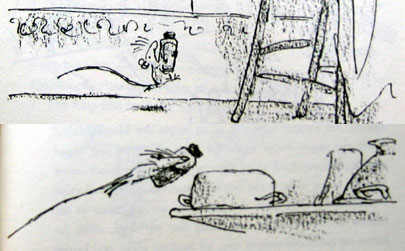

three hundred bucks. By the time I started reading the issues, the black-and-white comics and mini-comics boom of the 1980s had begun, and there were tons of imitators and spiritual descendants of the Turtles on the racks. What grabbed me about TMNT was the roughness and rawness of their art style, and the way that you could kind of see how they were done (though the toned paper that they used was awfully mysterious to me). I liked the idea that with some art supplies, some imagination, and fifty years of monster movies, samurai manga, and other comics to crib from, you could create an entire world.

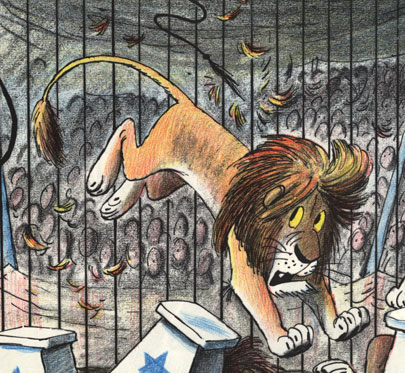

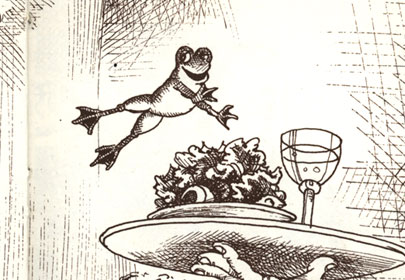

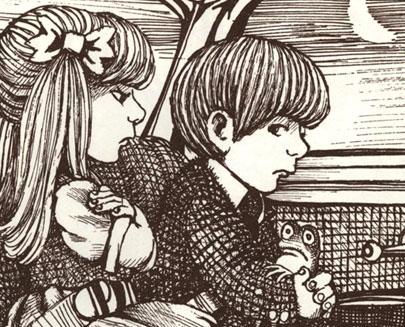

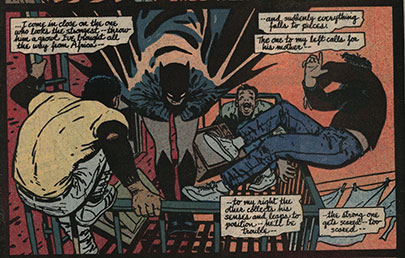

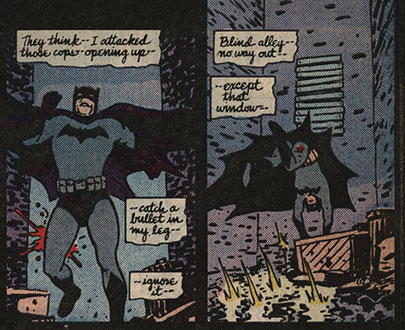

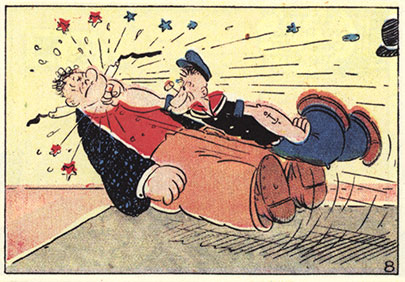

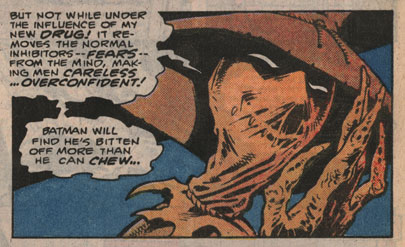

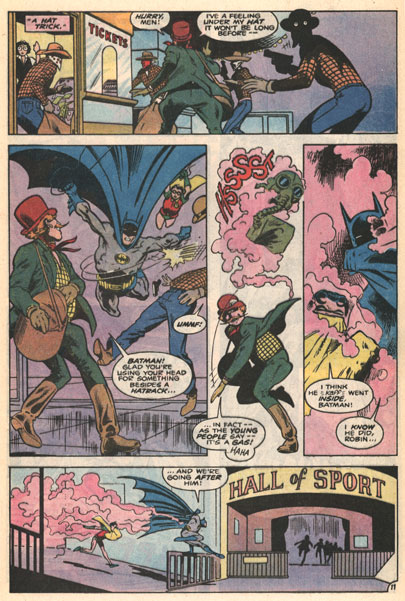

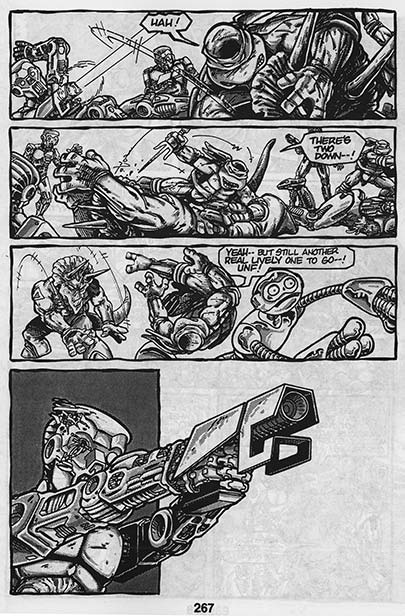

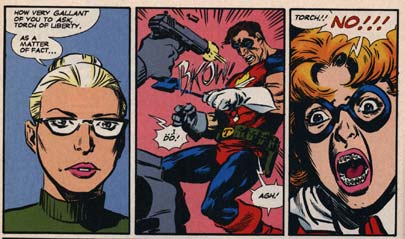

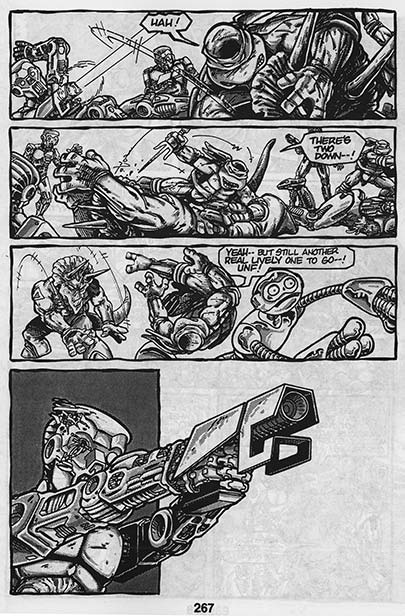

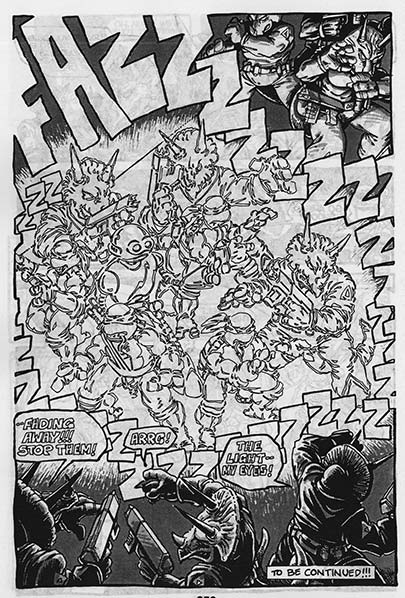

Kevin: I honestly can't remember how I got hooked on TMNT. My earliest memory is of sitting on a bus in New York and reading the "book 2" graphic novel. I'm flipping through it right now (not having done so in ten+ years) and every quip and sound effect is coming back to me. I think what hooked me on these turtles was that they were so REAL, at least compared to your standard superheroes. Flying guys in tights were a joke compared to these reclusive, aggressive thugs who bled when cut. So anyway, once I got the bug, my whole world revolved around the TMNT franchise. I spent a lot of my money on the toys, but I still remember being a snob about the comics, even at age ten. Actually, I don't remember knowing anyone else who read the comics; they all just seemed to be into the TV show and the movies. The thing that moved me about the comics was the perpetual dance everyone was always in during the fight scenes. No one could stay still. And there were so many weapons flying around, there was constant danger. I think that as a reader, I want a visceral connection to the action. So reading about fights involving guns or lasers never did anything for me because I couldn't relate to it. But watching sticks and fists and dirt flying around -- that pulled me right into the action.

Zander: I read somewhere that the paper that Eastman and Laird used (a special paper that would reveal one hatch pattern when painted with one chemical, and another, perpendicular to it, when painted with another) was so expensive that they cut the big sheets in half to save money. The result in the earlier comics was a chunkiness to the art and a slight inconsistency to the lettering that to me gave it a certain special vibe. Its lack of polish made it seem that much more wonderful; basically, it wasn't a quirky but average comic, but rather

the very best minicomic that had ever been made.

Kevin: I wasn't savvy enough then to appreciate how the comic was made. But I did appreciate the stocky muscular structure of the turtles. My first ever anatomy lesson was simply drawing those figures over and over again.

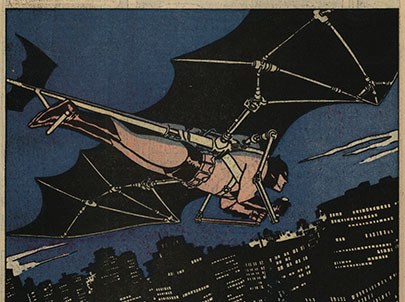

Zander: In addition to the fact that it was so accessible due to its amateurish surface, what I appreciated about TMNT was that within the art you could really see a solid understanding of light and shadow, as well as anatomy, architecture, etc. I loved that, like a lot of the other artists we've talked about in the Influences posts, these guys created a solid, weighty, deep world that you could imagine people (or mutated turtles) living in.

Kevin: Speaking of "these guys," I guess we should say a few words about Eastman and Laird themselves. I still to this day can't tell the difference between the two. "Eastman N. Laird" is one man as far as I can tell. Obviously I can see style changes as I flip through this stack of comics, but I can't tell what's Laird, what's Eastman, and what's simply changed over time. In 2001 I traveled with Zander to the San Diego Comicon and he, knowing I grew up with the Turtles, pointed to a guy wearing a black leather coat and said "That's Kevin Eastman." My jaw dropped for a few seconds and then I suddenly realized, "Hey, he's just a normal guy." But of course, I was still too shy to go up and say anything to him, at least nothing that he hasn't heard four billion times already.

Labels: Influences