I Wish Someone Would Invent: A Decent E-Economy

Have you ever thought about an invention that maybe YOU can't make, but it sure would be nice if someone else did?

No, I didn't stutter, I wish someone would invent a decent e-economy. That is, a way to buy and sell information on the internet that doesn't involve any physical media for a decent price. It's not too bad at the moment. iTunes is as good a way of buying music as any, I guess. It's better for TV shows and movies. I mean, a 48-minute TV show costs $1.99. A 3-minute song costs $.99. Come on! I don't blame Apple-- I know that the music industry has given them weird mandates that they can't really get around at the moment. But the problem with the e-economy as it exists now is that things cost way too much considering how little things cost to distribute and package as opposed to their real-world counterparts. But more to the point, it's too expensive considering how much people want to pay.

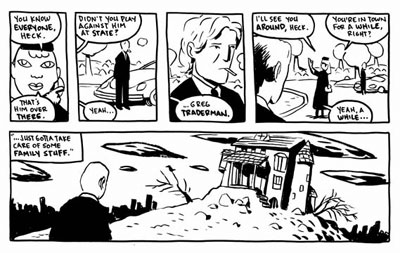

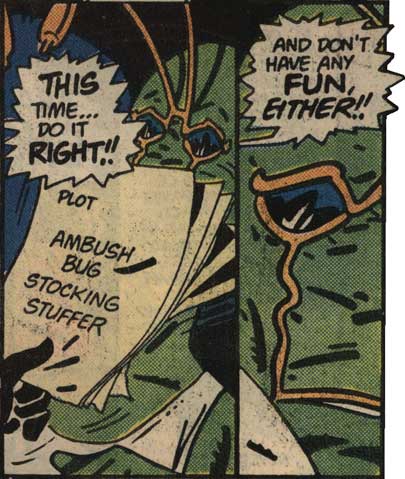

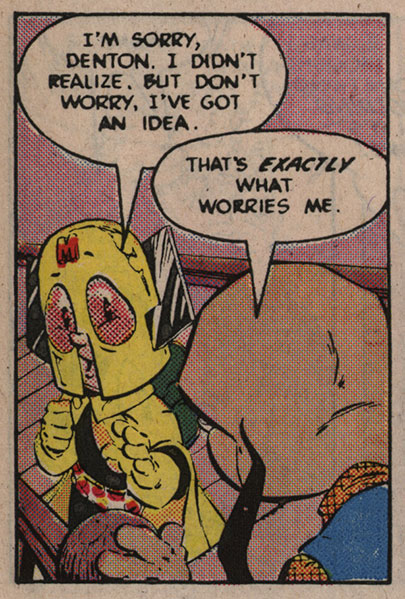

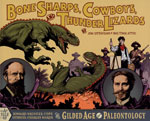

We've gotten past all serious talk of micropayments, apparently, especially with Bitpass going under. Bitpass was the first real payment system that allowed vendors to charge small amounts-- as small as a dime-- and they sold Scott McCloud's The Right Number for a quarter per chapter. The Right Number had chapters of about, say, 100 panels each: approximately what you'd have in a regular comic. I jumped at that because I'd been waiting for more McCloud stuff, and I was eager to see his philosophy jump to the mainstream-- the philosophy that large amounts of information should cost small amounts of money. But my thought was that it was a little expensive. It sounds strange to say, since obviously 25 cents is a very small amount of money, but really, 100 panels of free comics online is not exactly a rarity. Far Arden, just to choose an example. So I got it, and it was good (so far-- there's a third chapter that hasn't been done yet), but nothing about the transaction struck me as anything other than proof of concept.

I had some extra money on my BitPass account after that purchase, so I looked around for some other vendors that accepted it. One that interested me was called Dime Novels. A novel for a dime? Wonderful! I'll take it! But the thing was-- they weren't novels. They weren't even novellas. They were about ten pages long. With all the free stuff online and all the great content that people are putting up just for the heck of it, these were a total ripoff. If someone put up a hundred-page novel and charged a quarter for it, I'd get it just to see what it was about. I might not even read the whole thing if it wasn't that great, but I'd never feel like I'd wasted my money. The problem with these products is basically that they failed the sniff test. Does something seem like a great deal? Then people will buy it. Does it seem like it's barely worth it? They won't. 25 cents for a Scott McCloud comic is worth doing once or twice, but I'd start to feel like I was just throwing money away after a half-dozen, even if it wasn't that much money.

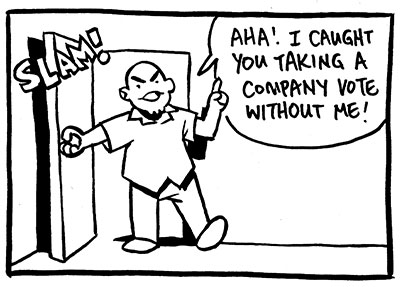

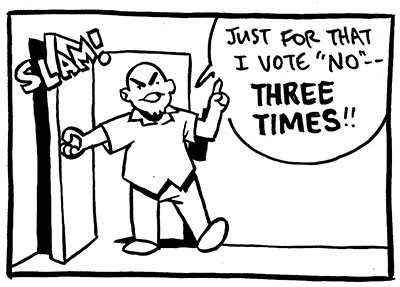

A lot of the talk about micropayments was about things like charging a tenth of a cent for a daily comic strip, but to me, that sort of thing just sounded like it would make a good portion of the web a giant pain in the neck. I liked the idea of charging a quarter for a LOT of content, rather than an infinitesimal amount of money for five seconds of entertainment.

Some people bristle at the idea of paying anything for content on the web, and I certainly understand that. There is the feeling that nothing is free anymore, and that browsing anything is a commitment. But I think that if vendors understand that they are competing with huge amounts of quality free material, they would quickly price themselves at a reasonable rate. Little things, like daily strips, would not last long as a paid commodity. But five years of that comic strip in a convenient file format for a quarter sounds like a pretty good deal. The money spent would simply be a small fee for not having to search the whole internet with a peer to peer client.

There are a lot of things to be had online that are not 100% legit that, if they were packaged inexpensively, and I mean REALLY INEXPENSIVELY, could be sold by the creators and copyright holders. One hundred issues of old X-Men comics in pdf format? One dollar. Fifty old-school arcade game ROMs? Five cents. All the Philip Marlowe radio dramas? Buck fifty. A Doc Savage novel? A dime.

It would take some experimenting to find that sweet spot where you're not just giving it away, and still attracting customers, and one might have to find some solutions for bandwidth (like BitTorrent), but isn't that the purpose of an economy? If those things are so readily available for so little money, who (in large numbers) would look for them illegally, except out of sheer cussedness? And (particularly in the examples I've given) if the material is old and out of print, there is little to keep publishers from putting it out there. In most cases they're not making money off it anyway.

Online payment systems, like PayPal, shouldn't have any barriers to transferring small amounts of money from one PayPal account to another-- it's just moving bits-- and charging a small percentage of the price as a transaction fee.

I mean, think about it. What are some big things you'd pay a dollar for?

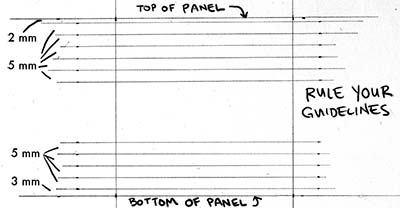

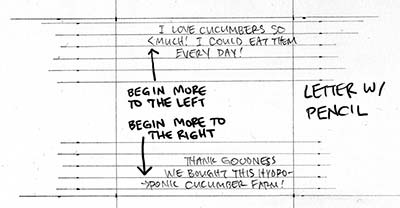

Scott McCloud's micropayment comic and micropayment essay

Sean Barrett's "upay" response

Labels: I Wish Someone Would Invent